For our themed column on Pavese’s contemporary critique, Iuri Moscardi interviewed professor Monica Lanzillotta, author of recent “Cesare Pavese. Una vita tra Dioniso e Edipo”.

You focused on Pavese in multiple ways (articles, books, book reviews). How did this attraction towards Pavese’s works originate?

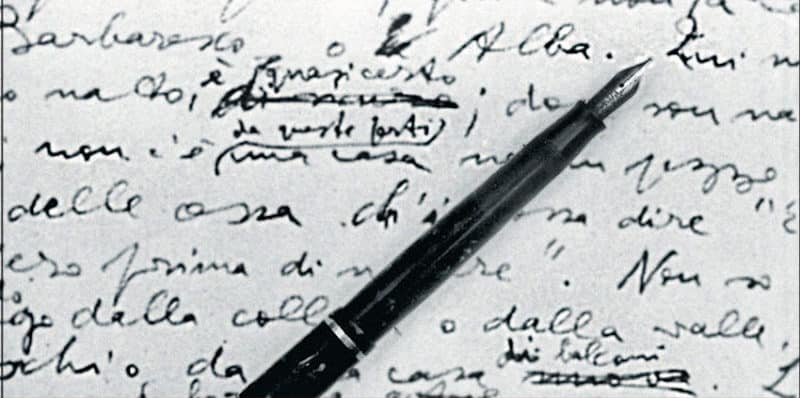

I read and loved Pavese’s works when I was a teenager, and for this reason I wrote my Master’s thesis on him in 1992, when it seemed that scholars began to lack interest on him. Then, I continued to study Pavese, attracted by his job as an editor and translator and by his Dialogues with Leucò: I published these reflections on him, from 1995 to 2023, in books and articles, among which in 1999 the first complete bibliography on Pavese (Bibliografia pavesiana). I have also organized the conference Cesare Pavese tra cinema e letteratura (Cesare Pavese Between Cinema and Literature) in 2011.

The element of Pavese that has always attracted me was his poetic, which can be summarized in the term “monstrous”. In the ancient Greece, this term referred to hybridity, the co-presence of the contraries. For instance, in a note from his diary on 24th February 1947, Pavese wrote, referring to his Dialogues with Leucò: «The monstrous and golden era of Titans was the age of undifferentiated men-monster-gods. You have always considered reality as a titanic idea, or rather as a human-divine Chaos (=monstrous), which is the perennial form of life». The basic semantic of Pavese’s universe is constituted by the two poles of childhood and adulthood. The keywords “countryside/Titanic-Dyonisian/first time” relate to the former, and “city/Olympian-Apollonian/second time” to the latter. These keywords do not contrast but coexist (childhood in adulthood, countryside in the city, etc.) since Pavese’s earliest poems and proses. Pavese’s predilection for the category of the monstrous is mirrored, at a thematic level, by the choice of threshold, periphery, and hybrid identities (phytomorphic and theriomorph beings, feminine men and masculine women are frequent in his works); at a formal level, it is expressed through anthropomorphic metaphors and synaesthesias.

Other elements that attracted me were the structural ingredients of Pavese’s poetry and prose, which marked his distance from Neorealism and Hermeticism movements, predominant in the years when Pavese was working. He avoided objective description and action (telling what a character is doing), he did not create characters, but made the rhythm of the interior life in its development (the stream of consciousness) the topic of his narration. Pavese’s plots lack facts and actions and rely on some structural elements: image-stories (through the connection of images the reader discovers the symbolic plot, a tale within the tale), epithets (other forms of tale within the tale, suggesting the secret reality of the character), and dialogue (in many pages of his diary, Pavese focused on meditations about dramatic art, especially of Ancient Greece, Shakespeare, and cinema). For him, art has magical and ritual origins, and his works are characterized by hurried setting and schematic dialogues, as it happens for fairy tales, legends, and myths, and by repetitions and reversals, like swimming. The protagonist of Pavese’s plots has to deal with the recovery of childhood through memory and with the awareness of his destiny. He can discover his real identity only by retracing the fundamental steps of his childhood and adolescence, enlightening the present through the resurfacing of the past.

Your latest book, Cesare Pavese. Una vita tra Dioniso e Edipo, is a complete study of Pavese’s work, analyzed through the two categories of Dionysus (childhood, irrationality) and Oedipus (adulthood, destiny). Why did you choose them?

Pavese’s poetic is based on two poles: childhood and adulthood. Childhood is the age of primitive mentality, the primordial space of the origins when the child lives by mixing animal and vegetal worlds without any contrasts. Childhood is the instinctive-irrational period when we learn how to discover the world by purely absorbing it, by defining it in images (hill, house, tree, etc.) that constitute the molds of our knowledge. For Pavese, the will of the adult is conditioned by the choices made by the child in an irrational state: childhood is the early determination of destiny. Pavese’s works focused on the resurfacing of the blotted-out origins (the “first time”) and on the return (the “second time”), which is necessary to understand our real identities. The entire work of Pavese is centered around the cognitive investigation that progressively brings the character to discover the destiny, the subconscious force that moves him towards one direction, the origins.

The myths behind Pavese’s stories are the myths of Dionysus – representing the constitutive stage of childhood, the undifferentiated chaos, the monstrous because contraries coexist in him (he is at the same time a god and a man, a man and a woman, an animal and a plant, etc.) – and Oedipus as celebrated by Sophocles, when he discovers that he has become parricide-regicide and he has married his mother because this is his destiny (everything had already been established during his childhood). I chose Dionysus and Oedipus to represent Pavese’s entire poetic because he read and translated Greek and Latin classical authors: he relied on them to support his poetic of the myth. The texts by Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides, Pindar, Plato, Herodotus, and Thucydides that he owned are densely annotated and the majority of his reading notes relate to passages centered on destiny. The relevance of classical literature was emphasized by Pavese in his famous Interview at the Radio when he said (talking in third person): «Pavese’s readings are first classical, then foreign, and finally Italian. Pavese considers Herodotus and Plato the best among Greek narrators (he does not make any distinctions between theater and narrative) […], writers who do not focus on the character […] but on the rhythm of the events and the intellectual-symbolic construction of the scene».

In the introduction to this volume, you wrote that Pavese eludes any literary labels; if anything, he might be “included in the larger category of Modernism”. I believe that studying Pavese as a Modernist would be fruitful: what are the Modernist elements in Pavese and why has he not been studied from this perspective yet?

Compared to his contemporary writers, Pavese eludes any early 20th-century literary label. He kept himself separated both from the progressive ideology of Neorealism (the so-called engaged literature) and the exaggerated subjectivism of the avant-garde movements. He can be considered as a Modernist writer because different traditions (from Greek and Latin classics to the modern Anglo-American literature, from ethnology to psychoanalysis) merged in his poetic, which becomes a system of thought that refuses the boundaries between cultural belongings. Pavese modernized literary genres and narrative processes through theater and cinema techniques (he mastered the dramatic dialogue) and the universal languages of mythology, clothings, flowers.

In the book, you used the category of “family novel” to describe some of Pavese’s works. What does this category mean and why did you think it would be appropriate for the analysis of many of Pavese’s works?

The “family novel” is a literary genre, very popular both in classical and modern literature. Suffice to mention, among the books loved by Pavese, the Greek tragedies narrating Oedipus and the Labdacus family, Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov, Mann’s Buddenbrooks, and Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath. Pavese also reconstructed the story of some families through consecutive

generations, focusing on the relationship between relatives, starting from The South Seas, a poem dealing with the relationship between the protagonist, his cousin, and other ancestors. As I tried to explain in the book, we can define The Devils in the Hills, Among Women Only, and The Moon and the Bonfires as “family novels”. In the last one, considered Pavese’s masterpiece, the problem of identity is the thematic center of the novel because the orphan Eel, in search of his real parents, intertwines his story with other five families: the family of Virgilia and Padrino, his adoptive parents, and their two daughters Angiolina and Giulia; the family of sor Matteo, whose first wife gave him two daughters (Irene and Silvia) and whose second wife gave him another daughter (Santina); the family of Nuto, who became a carpenter like his father; the family of the Knight, marked by his son’s suicide; finally, the family of Valino, whose wife Mentina gave him the son Cinto dying shortly after, and who is now living with his mother-in-law and his sister-in-law Rosina in an incestuous relationship.

This book analyzes all of Pavese’s works. In the essay you wrote for Cesare Pavese Mytographer, Translator, Modernist, the book I edited, you analyzed the prostitute in the entirety of Pavese’s work. Many scholars focused not on single books but on Pavese’s entire work. Do you think that this happens because Pavese can be understood only when we study his entire production? Can we separate his life from his work?

Pavese can be better understood if we read all his books because he is the typical example of what Lejeune called “autobiographical space”: he built his own image of man and writer through all the texts he wrote (both private and public writings). If singularly analyzed, these texts are not biographically faithful but in their reciprocal exchanges, in the space reserved to them, they define the complete image of Pavese and do not reduce his complexity nor fixate it. Pavese theorized the “monotony” (Narraring is Monotonous is the title of one of his most famous essays) because the main topics of his poetic are present since his juvenile production: he does nothing but detaching “pieces” from the big monolith and studying them under all the possible perspectives. Pavese has always considered monotony as the necessary condition for the validity of a work, so we need to read all his books to understand him correctly. The figure of the prostitute is a monotonous theme, too: it is present in all of Pavese’s works, from his juvenile poems until The Moon and the Bonfires, as I have tried to prove in the essay The «donne vestite per gli occhi» in Cesare Pavese’s Creative Production. In defining the prostitute, Pavese seems fascinated by Baudelaire’s The Flowers of Evil (he translated the poem L’Idéal from this collection in May 1928) and Sbarbaro’s Pianissimo. I have published an essay in 2017 in which I

studied the relationships between the two poets and in which I also inserted an unpublished correspondence.

“Un Pavese ci vuole”: this misquotation from a very famous passage from The Moon and The Bonfires was the title of a series of video-interviews I conducted with the director of Fondazione Pavese, Pierluigi Vaccaneo. Seventy-three years after Pavese’s suicide, do we still need him? And, whether yes or no, why?

We need Pavese because he is a “classic”; classic writers never stop to talk to men from all over the world. Pavese’s fame is internationally widespread: he has been translated and studied in countries that are far from the Italian culture and he is now part of the general knowledge also because of the cinematographic and musical cultures. In his creative plots, he used – as I have tried to explain in my book – the universal languages of mythology, clothings, and flowers.

An interview by Iuri Moscardi

Dialogues with Pavese: Tommaso Munari

For our themed column on Pavese’s contemporary critique, Iuri Moscardi interviewed Tommaso Munari, author of a recent essay on the history of Italian publishing.

Dialogues with Pavese: Sara Vergari

For our themed column on Pavese’s contemporary critique, Iuri Moscardi interviewed Sara Vergari, author of the essay Un “Pavese solo”.

Dialogues with Pavese: Lawrence Smith

For our themed column on Pavese’s contemporary critique, Iuri Moscardi interviewed once again Lawrence Smith, this time about his English translation of Cesare Pavese’s degree thesis.