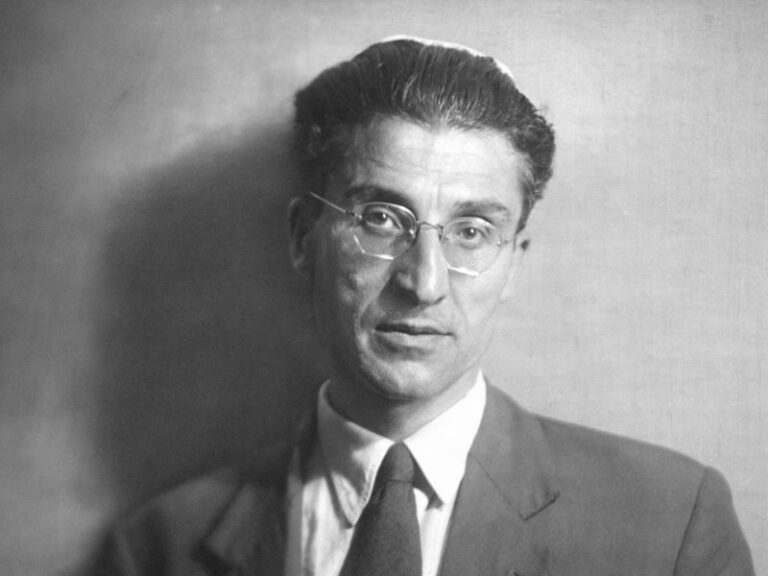

Cesare Pavese: life and works

Cesare Pavese was a poet, writer, translator, publisher and literary critic. It is considered one of the greatest and most influential Italian intellectuals of the 20th century. He was born in Santo Stefano Belbo – a small village in Piedmont’s Langhe – in 1908 and took his life in Turin in 1950, two months after he had won the Strega Prize, the most prestigious literary award at the time. Here you can find a series of interviews with those who have know him personally, some biographic notes and additional material on his life and work.

Franco Ferrarotti. A conversation about Cesare Pavese

Sociologist Franco Ferrarotti recalls his friendship with Cesare Pavese in a conversation with the director of Fondazione Cesare Pavese, Pierluigi Vaccaneo.

Lorenzo Mondo. A conversation about Cesare Pavese

Recently passed away, writer, literary critic and journalist Lorenzo Mondo shares his memories with Chiara Fenoglio, jury member of the Pavese Prize.

Carlo Ginzburg. A conversation about Cesare Pavese

Historian Carlo Ginzburg, son of Leone and Natalia Ginzburg – among Pavese’s closest friends – in an interview by Giulia Boringhieri, jury member of the Pavese Prize.

Cesare Pavese's life

The Langhe, the place of mythos

Cesare Pavese was born in Santo Stefano Belbo on 9 September 1908, in what was his parents’ country house. Even if he spent most of his life in Turin, the Langhe represented the place where he belonged and the mythical universe he drew from to develop his literary work. Santo Stefano Belbo, a small Piedmontese village between the Langhe and the Monferrato, was for him a place to leave and return to, in a constant search for a human and poetical identity. “One needs a village, if only for the pleasure of leaving it. A village means that you are not alone, that you know that there’s something of you in the people and the plants and the land that even when you are not there keeps awaiting you” (from the novel The Moon and The Bonfires, set in Santo Stefano Belbo). If you are looking for an unusual perspective on these places, watch our series Io vengo di là

His passion for American literature

It was 1932 when Melville’s Moby Dick was first published in Italy by Frassinelli Tipografo Editore, translated by Cesare Pavese for 1000 lire. At the time, Cesare Pavese was a young American literature enthusiast. He started his journey of discovery and dissemination of overseas literature with a dissertation on Walt Whitman, in 1930. Throughout the years this activity, among his many others, led him to approaching the publishing world, becoming editor-in-chief at Einaudi. For an in-depth analysis of Cesare Pavese’s passion for American culture and literature, watch the third season of Io vengo di là. If you want to dive into unexplored aspects of Pavese’s work as a translator, watch this video by Iuri Moscardi on the Molina fund, a recent acquisition of the Pavese Museum.

Cesare Pavese’s Turin

The core of Einaudi’s publishing structure took shape in the ‘20s, on the desks of Liceo Ginnasio Massimo d’Azeglio in Turin, where the anti-fascist intellectual Augusto Monti was teaching. His alumni collective used to gather at Caffé Rattazzi or in their respective homes to talk about politics, philosophy and literature. The group was composed of Leone Ginzburg, Massimo Mila, Norberto Bobbio, Giulio Einaudi, Cesare Pavese and others. If you want to find out more about Pavese’s juvenile friendships, watch our interview with Giuseppe Vaudagna, one of Pavese’s schoolmates at Liceo D’Azeglio.

But Turin, for Pavese and his mates, was not just linked to education and political unrest. They loved the city, its boulevards, the Po river, its hill, its inns called Far West and its cinemas where American movies played. “My lover, not a mother neither a sister”, this is how Cesare Pavese used to describe his relation with the city.

The confinement

Cesare Pavese got into this cultural and political atmosphere. Despite his contradictory attitude towards his mates’ positions – he had subscribed to the Fascist national party so that his sister Mary could teach in public schools – in 1935 he was arrested for a transit of letters from his house that were addressed to Battistina Pizzardo, a Communist activist he had an affair with. Pavese passed from prison Carceri Nuove in Turin to prison Regina Coeli in Rome. He was sentenced to a three-year confinement in Brancaleone Calabro (1.385 km from Turin) and expelled from the National Fascist Party. Following a pardon claim, two years were remitted, so in 1936 he could come back to Turin. If you want to know more about the places of Pavese’s confinement, watch the third season of Io vengo di là

His work at Einaudi

On 1 May 1938 Pavese officially became an editor at Einaudi. The directorate was composed of Giulio Einaudi, Leone Ginzburg, Giaime Pintor, Carlo Muscetta, Mario Alicata and other collaborators, including Norberto Bobbio, Elio Vittorini and Natalia Ginzburg. The directorate marked the, yet informal, beginning of the editorial meetings and decision-making processes of the publishing house, coordinated by Pavese. This is how Pavese’s long work-life experience at Einaudi started.

“For many years he hadn’t wanted either to submit to working hours or to accept a defined profession” Natalia Ginzburg recalled “but when he eventually accepted to sit at a table, he became a tireless and meticulous worker. He barely ate and never slept.” Rumour has it that the day after the bombing of Einaudi’s headquarters in Turin in 1942, he was at his desk just like every morning, after having removed the flakes of plasters.

Pavese’s contribution in the development of Einaudi’s series was influenced both by his own personal interest and the internal management dynamics of each series. For each of them he took on in fact different tasks and responsibilities and at various levels: from the organizational coordination to collective decision-making processes, from epistolary contacts with the authors to the recruitment of collaborators, from the choice of the texts to the supervision of the publishing house’ letters, translations, introductions and prefaces, and of the entire typographical process.

For Pavese the publishing house became everything. In that familiar place, the writer shared participation, harmony, commonality – yet among fits of rage and spites, often ironically described in his correspondence with Giulio Einaudi.

One of his closest relations was the one with Fernanda Pivano, at the time a young student preparing her dissertation in English Literature. That moment marked the beginning of a long friendship that led Pivano to translating and publishing The Spoon River Anthology for Einaudi under Pavese’s supervision, in 1943. Watch the episodes of Io vengo di là about the Turin publishing house

Einaudi’s series

Among its main series, I Saggi (Essays – launched in 1937), I Narratori stranieri tradotti (Foreign Novelists Translated – 1938), I Poeti (Poets – 1939), I Narratori contemporanei (Contemporary Novelists – 1941), L’Universale Einaudi (Einaudi Universal – 1942). I Coralli (The Corals) was launched in 1947. It was a series composed of emerging Italian authors somehow in continuity with I Narratori contemporanei, but with a more consistent concept. I Millenni (The Millenniums – 1947), developing around the American and Homeric myths, stood out among the most authentically Pavesian series, even if what mirrored his interests the most was La collana viola (The Purple Series – 1948). It gathered authors and texts related to the writer’s personal research – a collection of ethnological and psychological texts with an extremely irrational character – and it was also the series that absorbed the last years of his life and work.

His last years

Pavese experienced a progressive detachment and a growing autonomy from the literary culture of his times, from contemporariness and current events, fueled by an increasingly strong interest in ethnology and the poetics of classics and mythos. His attitude towards fame was equally peculiar. Natalia Ginzburg recalled that in the last years he had become a famous writer and this hadn’t changed anything either in his habits or in the scrupulous humility of his daily work. In various letters to friends and colleagues, the assignment of the Strega Prize in June 1950 was commented by the writer as a “sad affair”.

In his last years of activity, from 1948 on, a young man joined the publishing house and was taken under Pavese’s wing. He was Italo Calvino, whose great intelligence and lightness in writing is immediately noticed by Pavese. The young writer was always devoted to Pavese, who represented his reference point in Turin and his greatest master in writing, work and critical thinking.

In 1953 he wrote on Il Forestiero, in Turin: “It is true that his books are not enough to fully describe him: since what was fundamental of him was his example at work, the way in which the culture of the intellectual and the sensitivity of the poet turned into productive work, into values for all, into organization and exchange of ideas, into practice of and training ground for all the techniques a modern cultural civilization is made of.”

Cesare Pavese committed suicide in the night between 26 and 27 August 1950, in Turin. It was Calvino who took over his job at the publishing house without ever forgetting the lesson of his master.