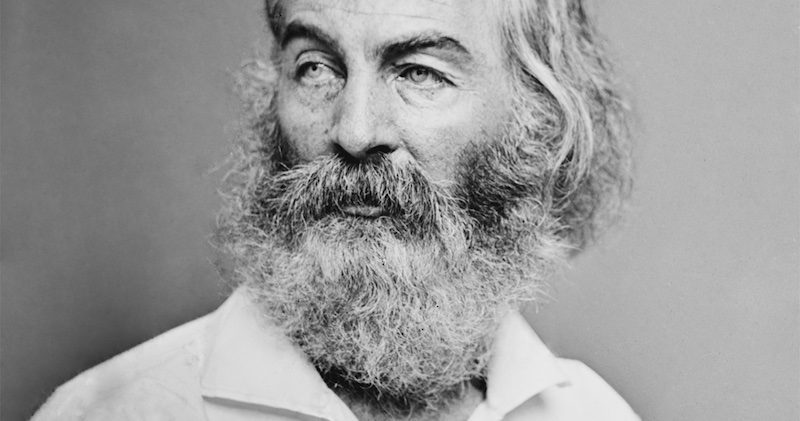

Beyond national borders, in search for interconnections and mutual influences: Caterina Bernardini presents her decade-long research on the Italian reception of Walt Whitman, subject of Cesare Pavese’s dissertation.

In your book, you focused on many, important, and different, authors and intellectuals: Giosuè Carducci, Ada Negri, Gabriele D’Annunzio, Giovanni Pascoli, Sibilla Aleramo, Dino Campana, and the Futurists. I didn’t know that Whitman had such an influence on so diverse authors.

Since I was in high school, I have always liked studying literature’s critical and creative reception (or what in classics studies is called “fortuna”). When I discovered that, differently from the situation for France, Germany, the UK, and other countries, there wasn’t any monograph on Whitman’s Italian reception, I started working on it, reading the existing scholarship and exploring archives and collections throughout Italy (from D’Annunzio’s Vittoriale; to a small library in Agnone, Molise, where Whitman’s first translator, Luigi Gamberale, lived; to Carducci’s house in Bologna; and the Aleramo collections at the Gramsci Foundation in Rome). There were, though, excellent shorter studies and articles and a few theses that greatly helped me get started and to which I owe a lot: one of the pioneers was my advisor back in Italy, Prof. Marina Camboni, and scholars like Roger Asselineau, Mariolina Meliadò Freeth, Caterina Ricciardi, and Grazia Sotis, among others, greatly contributed to the topic. As you pointed out, Italian writers appreciated Whitman for different (and sometimes opposite) reasons, but as I suggest in my book, Whitman’s work was inspiring as it provided the honest acceptance, exposition, and actualization of a common expressive problem: how to sing a modern identity in constant evolution? How to show its complicated, multisided nature?

This expressive problem resonated deeply in post-Risorgimental Italy. Every writer investigated this fundamental question when appreciating Whitman, and at the same time they applied the question to their interests: Carducci (who studied Whitman’s poetry with the help of an English teacher, who was often drunk and had been a soldier in the American Civil War) was struck by Whitman’s modernized diction and free verse – which at the same time was capable of echoing classical, epic poetry. Negri saw in his celebration of the divinity and dignity of all people an expression of the socialist causes she ardently fought for in her early career. D’Annunzio found in Whitman a post-Risorgimental magniloquence and iconoclastic approach that led to his celebrations of hyper-nationalism (he cited Whitman during the Fiume blockade). Pascoli had a sophisticated understanding of Whitman’s rhythmical and musical components that contributed to his own innovations in this direction. Aleramo reinvented Whitman’s transcendentalist emphasis on spiritual growth and the need for individual emancipation. And Campana – who opened his first letter to his soon-to-be lover Aleramo by mentioning Whitman, and who took Leaves of Grass with him on his trip to South America – had a deep appreciation of Whitman’s mythopoetic and messianic writing about American lands, and he adopted a number of Whitman’s formal innovations (such as the use of gerunds, present participles, and of nominal style).

But as much as it is important to see how different Italian writers adapted Whitman’s poetry to their specific agendas, my book demonstrates how it is crucial to remember that the reception of Whitman in Italy is part of a much larger network that involves other countries: for example, the first editions of Whitman that penetrated Italy were not American, but the British selected editions by William Michael Rossetti. And the mediation played by French criticism and vers-librism, Spanish modernismo, and Russian Symbolism and Futurism – all of which shaped the understanding and transmission of Whitman’s messages – had deep and complex effects on the Italian reception. In this sense, my book discusses a constellation of pre-modernist and modernist sensibilities as seen via Whitman, and it attempts more largely to trace a history of transatlantic modernism.

The final chapter of the book is entitled Cesare Pavese’s Whitman. The “Poetry of Poetry Making”. You mentioned how Whitman fascinated Pavese as much as Papini: in other words, not only anti-Fascist intellectuals were attracted to American literature. Is Whitman really an icon for American literature? Or wasn’t he a multifaceted, controversial figure, who for this reason attracted different intellectuals?

I think these two questions are not opposite to each other but co-dependent: Whitman is an icon, and much more so because he is multifaceted and controversial. By being a working class, self-taught and queer, experimental but accessible poet of the “and and” and not of the “or…or,” Whitman embraces and obsessively tries to give voice to all sides (with many and serious, problematic shortcomings of mis- and under-representations). He tried to pierce loudly through the cultural and literary norms and elites of his times toward the future, more inclusive times that he envisioned via his writing. These characteristics were (and are) appealing for admirers in very different contexts. The case of Papini and the Futurists is particularly interesting, and it should also be seen not monolithically as solely a case of pro-Fascism.

Papini’s admiration for the American bard started in the circle of La Voce, where Campana and Piero Jahier also gravitated (and these latter did not have any Fascist understanding of Whitman: in fact, Jahier re read Whitman in anti-Fascist terms). But Papini’s take on Whitman, which had started with an emphasis on democratic universalism (and even with a comparison of Whitman to Saint Francis of Assisi) soon changed and became imbued with Nietzschean-charged concepts of masculinity and critiques to the “soft” Italian bourgeoisie that were similar to some of the Futurists’ approach to Whitman. These latter (also via French vers-librism and via the guiding role of, among others, Gian Pietro Lucini) had deeply understood the revolution of Whitman’s free verse, but later on they fully (mis)appropriated Whitman’s iconoclastic tones for their militarist agenda and their celebration of violence: Whitman’s catalogues and energizing diction were brought to the extreme. But we must remember that some Futurists always refused to do this: in the book I discuss, for example, the case of Mina Loy, who concentrated instead on Whitman’s liberating depiction of sexuality and experimental use of polyglossia. Again, writers read and echoed Whitman’s work by emphasizing (and sometimes heavily distorting) the aspects that most appealed to them.

What was the role that Whitman really played for Pavese? Pavese wrote his thesis on his poetry, but he never translated the Leaves of Grass. Your chapter seems to reconsider other scholars and critics who considered Whitman excessively influential for Pavese’s poetry.

I think that Pavese deeply loved and understood (much better than a lot of other Italian and international writers and scholars) the nature and value of Whitman’s work. He was at first drawn to Whitman’s lyrical I’s confident tone and the absence of any moralism, which was an important lesson for Pavese to receive at the very young age (during high school years) when he encountered Whitman’s work. He then gradually gained a finer grasp of Whitman’s linguistic and poetic revolution: the use of slang and colloquialisms, the tone of pioneering vitality, the explicit anti-literariness and originality of forms and themes, and the general meta-poetical and modern nature of Whitman’s writing which, in an unforgettably cogent formula, Pavese summed up as “the poetry of poetry making.” But, in my opinion, if it is true that Pavese finely understood Whitman’s poetry (although not without any shortcomings: the biggest one being the lack of any discussion of homoeroticism in Whitman’s poetry), it is also true that Pavese fully absorbed Whitman’s ultimate lesson to poets who would follow him, i.e. to pursue one’s own originality, as clearly communicated by the speaker in Whitman’s Song of Myself: “He most honors my style who learns under it to destroy the teacher.”

In other words, Whitman contributed to push Pavese toward finding his own style and creative landscape as a writer and to embrace and celebrate the radical difference of it, but Pavese’s poetry remains quite distant from Whitman’s. As Pavese writes in Il mestiere di poeta (the appendix to Lavorare stanca), he intended “each poem as a story.” This narrative quality is almost never part of Whitman’s poetry. Pavese also never recurs to catalogues. And as he clarified in the same essay cited above, the free verse Pavese employed is not like Whitman’s, but rather his personal re-elaboration: as he put it, “every poet re-creates in himself the interior rhythms of his imagination.” I also think that critics have focused too much on how Whitman may have been influential for Pavese’s depictions of nature: Whitman’s adoration for cities (and New York in particular), the inebriating sense of being part of a bustling crowd, and the importance assigned to focusing on ordinary people in urban settings was just as inspiring for Pavese (there are beautiful passages about this in Il mestiere di vivere).

In your study you mentioned the role of Pavese as a translator of American authors: he was a pioneer for the closed horizon of Italian literature. Nevertheless, his “American myth” ended after the Second World War, with Pavese’s bitter remarks about the lack of vitality coming from there. As an Italian living in the US, what is your impression of the American literature today: has it recovered this vital and inspiring role?

I think that the American literary production, both in poetry and prose, and both for mainstream and more niche audiences, has continued to be of high quality and in this sense also inspiring and groundbreaking. Creative writing has always been given lots of support and funding by universities and various public and private institutions, which has helped. There are lots of new writers right now that are trying out new things and powerfully tackling uncomfortable truths (I am thinking, for example, of Tommy Orange’s There There). But I have to say that, as a scholar, I am really striving to do away with our ideas of borders when it comes to literature, and to show that we need to re-think and undo notions of nationality to understand literary works, especially in our globalized and interconnected world. My book argues that we cannot study the Italian reception in isolation, and I think that it is not useful to consider American literature in isolation either. Every work of literature, while bound to a context and a language of production, naturally depends on and participates in a much larger and transnational network of intellectual and creative artistic enterprise (the work of Wai Chee Dimock, among others, has greatly inspired me in this sense). I think that different literatures naturally influence and benefit from each other, and that writers inhabit and portray several cultures and subcultures. While we conveniently continue to label literatures under the same national umbrella, the reality is much more complex. One striking example in this sense can be found in Jhumpa Lahiri and the vital intermixing of Indian, American and, more recently, Italian cultures, that is at the core of her work.

Your book ends in 1945. If I asked you to go over that date, do you think you could find other authors who are still influenced by Whitman? For what reasons?

I think Whitman has continued to be a vital presence in the second part of the twentieth century and in our days. In Italy, in the last seventy years, there have been twenty-one new complete or selected editions of Whitman’s poetry: one every three years. In a 2017 study made by a famous Italian publishing house, a ranking of the best-selling poetry books in Italy in 2016-2017 saw Whitman at number twelve. And poets like Mariangela Gualtieri, Roberto Mussapi, and Franco Buffoni, among others, have directly echoed his work. I think that Whitman’s poetry continues to appeal because it sings the joys, wonders, struggles, and dilemmas of existence in both its physical and spiritual dimensions (two dimensions that can never be separated in Whitman), and because it pursues and enacts the liberation from having to concentrate on “proper” subjects and to think and live in certain, pre-assigned ways. It is also a poetry that speaks to readers because, more than others, it acknowledges the presence and importance of readers, and it asks for (and even depends on) their direct involvement: readers are constantly pushed to work on extracting personal meanings and to keep interrogating those same meanings. But it becomes more difficult to ascertain and discuss the direct weight of his work on writers who may have also read, for example, other internationally renowned writers like Jorge Luis Borges, Pablo Neruda, José Martí, Allen Ginsberg, or Fernando Pessoa, who were, in their turn, admirers of Whitman. Again, ideas of network and transnational circulation (and re-circulation) come back and need to be taken into consideration.

“Un Pavese ci vuole”: this misquotation from a very famous passage from The Moon And The Bonfires was the title of a series of video-interviews I conducted with the director of Fondazione Pavese, Pierluigi Vaccaneo. Seventy-two years after Pavese’s suicide, do we still need him? And, whether yes or no, why?

Absolutely, we still need Pavese. I think that the narrating and lyrical gaze of Pavese is truly one of a kind: a lucid but fiercely poetic observation that starts from the I and the its reflections on memory and sense of personal growth to become other and to diffuse itself into being one and the same thing with the earth and its colors and smells, the seasons, and the ancestral condition of being

human. I am fascinated by Pavese’s rhythm, the equalizing sympathy expressed with authenticity – never with pity or condescension – for common people, for all people, with their customs, wits, desires, and frustrations, and the constant sense of mystery and ultimate inscrutability that pervade his work. This mystery leaves me wanting to go back to Pavese’s work and read it again: I think Pavese is a writer that one inevitably returns to. I am also intrigued by the continual dialoguing between different temporalities: Pavese’s stories are historically (and importantly) rooted in a present that reverberates with nostalgia, while also being a brave meditation on how to shape the future. And I think I share with Pavese and with many of his characters that simultaneous profound attachment to my origins and my native land and culture, while at the same time a steadfast curiosity for other lands and cultures. We should keep on reading Pavese because reading is always a good idea, as Nuto crucially tells Anguilla: “Sono libri […] leggici dentro fin che puoi. Sarai sempre un tapino se non leggi nei libri.” But, more importantly, we should continue to read Pavese because he continues to show us that, as he writes in the poem Grappa a settembre: “a quest’ora ciascuno dovrebbe fermarsi / per la strada a guardare come tutto maturi,” and that writing itself is a stopping and looking.

An interview by Iuri Moscardi

>> Read the other Dialogues with Pavese

Dialogues with Pavese: John Picchione

Cesare Pavese is a writer who leads us through the complexity of reality: read more in our interview with professor John Picchione.

Dialogues with Pavese: Giancarlo Pontiggia

For our themed column on Pavese’s contemporary critique, Iuri Moscardi interviewed Giancarlo Pontiggia, author of recent «Quel che è stato sarà». Un commento ai Dialoghi con Leucò di Cesare Pavese.

Dialogues with Pavese: Claudia Durastanti

The new season of our themed column on Cesare Pavese’s contemporary critique opens with writer and translator Claudia Durastanti. Read the interview.